Civic Tech, Community Organizations, and Engagement

Rogelio Alejandro Lopez

This past week on Thursday May 22, Emerson Professor and Berkman Fellow Eric Gordon led the first of a series of workshops surrounding the impact of civic media on communications and governance. The aim of these workshops is to bring together organization executives, local government officials, technologists, and academics to discuss the changing nature of community organizations and governance in light of emerging technology, in a hands-on and participatory fashion.

Over the course of the year, there will be two additional interactive workshops focused on evaluation and scale. The ultimate goal for these series of gatherings is to create “a network of practitioners and scholars invested in understanding emerging ecosystem of community engagement through and alongside technology.”

Eric kicked off the workshop with a round of introductions and a simple question that helped frame the event as a whole: What about technology makes you most anxious? The varied answers were very insightful, and they set the stage for the workshop:

- Not having the adequate technology for the task at hand.

- The rapidly changing nature of technology.

- The challenge of choosing which technology to invest time and effort into.

- New programming languages that emerge.

- The pace of change is faster than people’s ability to learn and keep up.

- Becoming overly dependant on tech savvy people to stay relevant.

- Working with others with low tech skills.

- Becoming overly dependant and “enslaved by tools.”

- Being required to innovate constantly and not having room to fail.

- Diminishing balance between work and home.

- Constantly feeling inadequate in terms of tech knowledge.

- An uneven distribution of tech capacity, with youth leading the charge.

- Not having the skills being shared around.

- Seeking technical fixes for problems that don’t have tech solutions; where the solutions are human.

- Higher tech tools may replace lower tech tools.

- Making smart decision about what technologies to adopt/build in personal and professional life.

- The need to find balance as a society for tech benefits and the drawbacks on privacy. Trying to reach people that are generally not engaged.

- Looking for large tech solutions instead of simple things.

- When tech is seen as a simple solution, when human intervention may be more important.

- Unequal access to technology.

- Technology overshadowing human agency.

- When online content is taken out of context.

- More needs to be learned before throwing tech tools at the world.

- Technology failing or not working properly.

- Losing the ability to have opinions independent of social media.

A presentation titled “Civic Tech, Community Organizations, and Engagement” highlighted the history of democratic governance in the United States. Specifically, Eric underscored how groups have historically formalized as a means to facilitate, empower, and represent citizens, ultimately to communicate and interface with governments. In the mid 20th century, groups and citizens formalized further to develop organizations, such as NGOs, Non-Profits, and Community Development Corporations. With these institutional models, organizations sought connections and placed emphasis on building relations with constituents using varying tactics: face-to-face, door knocking, flyering, community meetings, community socials, etc. These tactics have essentially formed a grassroots tradition, and identity, among long-standing community organizations.

Emerging technologies are altering how governance and communications function in cities: “Smart(er) Cities, focus on end user (“putting democracy in the hands of the individual”), filling the gap of public funding (“scalable tech is cheaper and more efficient.”).” A key question that Eric posed to the group was: “What changes in an organization’s mission and identity when digital technology is introduced? What changes in how people understand the civic association?”

A notable example of the intersection of technology and governance is Code for America, which has the dual effort of repairing government and repairing democracy. Specifically, Eric mentioned how Code for America aims to strengthen capacity within government organizations with new positions for the technologist, and by building “short term projects and long term capacity.” At the same time, building projects at scale can be a challenge when they are expected to “scale to the size of the internet.”

The unique properties of digital technologies, and their potential impact on civics, was exemplified through the Possum Story in Boston. The story involves Citizens Connect, a civic platform developed by the city to allow residents to report infrastructure damages and other areas for concern. A Boston resident used Citizens Connect to report a possum in her garbage to the city. However, instead of receiving action from the City of Boston, the resident’s neighbor saw the post on Citizen’s Connect and proceeded to lend a helping hand to remove the possum. The point of the possum story, mentions Eric, is how civic technologies are allowing residents to by-pass organizations, even government, to find solutions to everyday problems.

Another notable occurrence that drives this point home is hashtag activism, specifically the emerging ability to have large coordinate efforts around issues without direct organizational structures. The specific example referenced was the #bringbackourgirls campaign, a coordinated yet largely informal effort to raise awareness and mobilize support for the large group of kidnapped girls in Nigeria.

Both the Possum Story and #bringbackourgirls highlight the changing roles of organizations, specifically how coordinated efforts, both small and large, can bypass formal intermediaries altogether. In this sense, the dominant narratives surrounding emerging technologies, as potential conveners of netizens for the purpose of collaboration and engagement, seem to be pushing against those of traditional organizations. If this is the case, then what shall the role of the traditional organization be? Eric provided key questions in this area:

- What does technology do for organizations?

- How is capacity built within organizations?

- Who’s using technology?

- When does it get used?

- Tensions between grassroots and digital communication?

- Recognition that youth use technology differently.

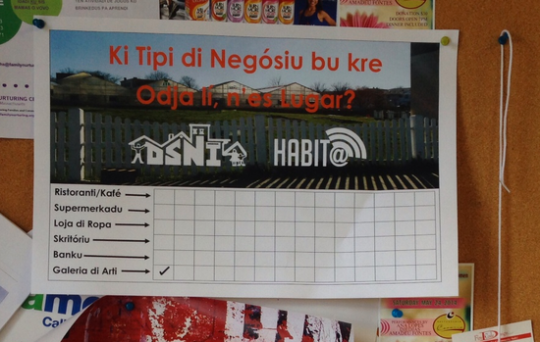

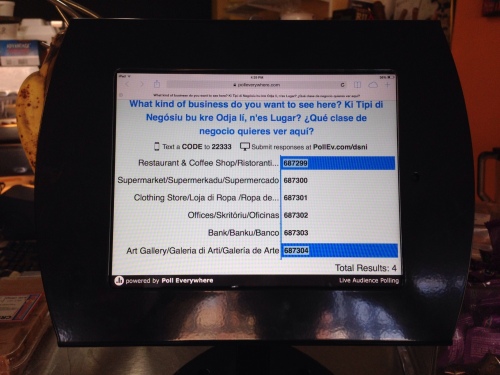

As an effort to answer these very questions, Eric introduced the Habit@ Study (link to blog), a project that aims to understand how community organizations are responding to technological change. The Habit@ Study has two major components: a deep focus on a single organization in Boston; “open-ended interviews with community organizations in four cities in the United States – Boston, New York, Los Angeles, Austin.

Following the overview of topics, workshop attendees were instructed to form groups in order to discuss the topics presented within the context of each individual’s organizational context. With roughly 25 participants in attendance, four groups of six formed, and an initial discussion question was posed: What is the role of (your) organization in the shifting communications landscape?

Before long the room became lively with discussion, as individuals took turns to describe their organizations, with specific attention to communications. As mentioned before, the perspectives shared matched the diverse professions and organizations of the attendees: technologists working with public school systems, local government professionals, and public sector practitioners, each shared their unique insights.

As the activity name implies, each group was specifically tasked with identifying key technology problems and challenges faced by their respective organizations. Each individual was required to identify and discuss the most pressing technology issues faced by their organizations. One participant mentioned experiencing frustration surrounding the push for tech literacy, when basic text literacy and even language barriers continued to be larger barriers. Another person underscored how necessary failure is to innovation, yet the space for failure is seldom aloud in government and the public sector at large.

After each individual got a chance to discuss their specific organizational challenges with technology, they were required to find the ten most common challenges faced by each group as a whole. As before, groups quickly organized their efforts and proceeded to arrange and categorize their most pressing issues (on stickie notes). Each group needed to determine the categories on their own, and it was interesting to witness how discussion led the task among groups.

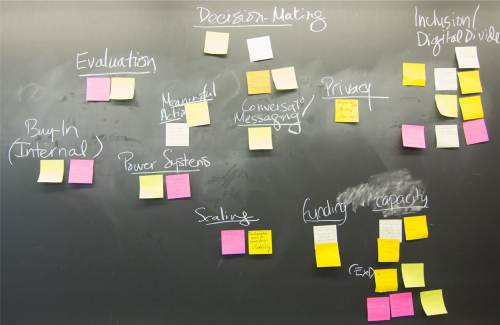

Once each group had organized their collective challenges, they were required to do the process yet again, but this time with the entire room. At first the stickie notes carrying the challenges were scattered as they were placed on a chalkboard, but they quickly took form as organizers emerged and began grouping by commonalities. The main categories, with corresponding challenges, were as follows (in no particular order):

Buy-In (Internal)

- Getting Buy-in on Tools

- Organizational Policies and how the deal with technology.

Evaluation

- Uncertainty about it effectiveness – Does it achieve intended goals/needs?

- General evaluation of tools

Power Systems

- Understanding of how systems works is required to effectively influence

- Forgetting human networks and interactions

Meaningful Action

- Easing boundaries between physical and digital space around participation

- Motivating people for meaningful action online

Scaling

- Appropriate use of technology, overuse, and information overload.

- The fundamental need for conversation about scalability.

Conversation/Messaging

- Coherent branding online

Decision-Making

- Dependence on optional decisions by the powerful

- Making civic participation tools effective and respectful, and connected to real decision making

- From broadcast role (1-way, government) to interaction and feedback

- Authentic 2-way conversations

Funding

- Having enough resources (time, people, money) to utilize tech for effective communication

- Funding/resources for tech

Privacy

- Access to data, privacy, and user adoption

Capacity

- How to get people to adapt to using tech – developing skills, overcoming fear, personally committing to change – within organizations

- Training and education on rapidly-changing technology

- Staffing to support tech

- Getting people to adopt the new system

- The need to build skills

- Rapid changes in technology, struggling to keep up, and slow adoption amongst institutions

- Organizational capacity lacking training and skills

- The challenge of tech implementation

Inclusion/Digital Divide

- If tools are too complex, then they constantly require help to function, instead of focusing on what those tools should be making easier

- Uneven access to technology reinforces inequity; engagement of all constituents must be ensured

- The constant use of the word “citizen” in this space excludes a list of people

- Continued digital divides and access issues

- Reaching new and existing audiences inclusively

- Language barriers

- Lowest-common-denominator thinking

- Access and literacy

- Tailoring the right message: languages, cultural diversity, education level, etc.

At the ending of the activity, Eric led a discussion surrounding the themes that had emerged. Many important points were raised in terms of privacy and security. In regards to engagement, one person said: “Participation is a finite resource, so online participation must be linked to decision making in order to be meaningful.” Another mentioned how the tools change the ways that we think about and approach existing and new problems. One salient point underscored how there are legal, moral, and ethical questions that are wrapped into emerging technology. Yet another attendee mentioned how the list was not surprising at all, since it reflected what he saw as general problems overall, relating or not to technology.

The mapped challenges directly informed the next activity, which was a custom tailored version of @stake, a game which simulates decision making and bargaining within organizational structures. For this version of @stake, groups needed to first determine an organizational profile that would inform decision making. For the purpose of the workshop, participants imagined the following organization:

- Location: Boston

- Size: 80 staff

- Mission: Public Health

- Prog Challenge: How we fit under the Affordable Care Act.

With this organizational profile in mind, the Engagement Lab team, led by Eric, played a round of @stake in order to explain how the game works. There are two types of players, one decide and the rest assume the role of imagined organizational characters. Characters are assigned by a deck of cards, with each card representing a character with a short biography and a set of agenda items. Some of those characters included IT Staff, Executive Director, Community Organizer, and Data Manager, each with their own set of priorities. One the deck of cards is shuffled by the decider, all other players must randomly choose a card and familiarize themselves with that character profile.

At the same time, the decider, who is also in charge of a bank (comprised of game pieces, in this case beans), places three game pieces into a central “pot” and gives three more to each player. The overall goal is to have each player (excluding the decider) pitch a solution in response to the challenges provided by the decider. Each player has 1 minutes to develop their pitch, from the perspective of their assigned character and corresponding agenda items. Each player then has 1 minute to deliver their pitch, with the option to extend their pitch by 30 second per each game pieces added to the pot by the players.

The section following individual solution pitches is the deliberation phase, which is essential a discussion “free-for-all” (players are allowed to interrupt each other) as the decider asks the players questions about their proposals. As before, players can add beans to extend the deliberation time. Once deliberation ends, the deciders selects the “best” proposal and the pot is awarded to the winning player. Other players can still receive points though, for each agenda item that is successfully incorporated into the winning proposal.

Based on the mapping of challenges from the previous activity, all groups needed to respond to three technology related questions when playing rounds of @stake (one per round):

- How do you effectively grow capacity to use technology in the organization?

- How do you engage the public in a way that satisfies federal requirements for inclusiveness while still taking advantage of the affordances of new tech?

- How do you empower people internally to be part of organization decision-making?

The many rounds of @stake, and the issues raised (both real and imagined), directly informed our closing discussion aimed to synthesize the most salient points. When directly asked about their experiences with @stake, one person mentioned how they wanted the game to tease out the relationships with organizations and cities more. At the same time, someone else wanted to get beyond organizational box (thinking). Another mentioned the how the most convincing proposals spoke to values: “I was more swayed by value statements than technologies.” To this, Eric mentioned the rhetoric surrounding technology, such as its ability to be democratic, that influenced tech solutions.

Many other important points emerged from the discussion:

- One person noted how the urgency to “keep up” with technology happens in other aspects of org no related to tech, such as themes presented by funders.

- “How do our organizations address problems in a technologically enabled world?”

- “At what point does technology actually help the organization in its mission, as opposed to just eating up resources?”

- “How do we understand how social media activity turns into meaningful action? Instead of focusing on what media affords, look further into the meaningful interventions that are possible due to new technology.”

- On failing, and the importance of being able to fail in the public sector, one person pointed out a salient contradiction – “You’re allowed to be ineffective, but never to fail.”

- Tech culture needs to be examined, since organizations try to superimpose tech values onto their organizations, but those values may not work or be compatible. The specific example mentioned was how not everyone could be like Google, with non-traditional organizational structures and cultures.

- Another observation provided was how people involved in civic technology usually aren’t meaningfully involved in civics.

- In government, solutions are often seamless, and there is an idea that solutions should not be disruptive to people’s lives. In the tech world, it’s so much about novelty, and less about seamless integration.

- Another person mentioned the desire to constantly relay information back to constituents, when people don’t always want to be constantly updated. This same speaker also mentioned how people in different positions should have more opportunities for interaction.

- “There was this big idea that civic hackers were going to change government, because tech cultures were not as inefficient as government. Certain sectors certainly are dysfunctional, but that does not mean that they don’t have meaningful contributions.”

Overall, the event was a meaningful kick-off to our series of workshops, which certainly served the purpose of bringing diverse perspectives together to discuss key challenges surrounding technology, community organizations, and governance. What’s more, the vast knowledge and experiences provided by participants directly informed and led conversations, and they represent a strong foundation for a network that can have meaningful impact in the Greater Boston Area.